PAC learning

Definition Consider a space $H$ of hypothesises.

This space is PAC-learnable if: for every $\epsilon,\delta \in [0,1]$, there exists an algorithm $L$ and parameter $m_{\epsilon,\delta}$ such that the algorithm $L$, given $m_{\epsilon,\delta}$ examples, returns with probability $\geq 1-\delta$ a hypothesis $h$ whose error rate is $< \epsilon$. When there exists a polynomial-time algorithm in $1/\delta$ and $1/\epsilon$ (so $m_{\epsilon,\delta}$ is also poly in $1/\epsilon$ and $1/\delta$), the space $H$ is effectively PAC-learnable.

Example Consider functions $R \to \mathbb{B}$ of the form $f_c: input\mapsto(true \text{ if } input \geq c \text{ else } false)$, they return true exactly on those inputs that are greater than some threshold constant $c$. Define $H$ the be the space of such functions.

Proof that H is effectively PAC-learnable We show that arbitrarily choosing a function between the largest negative and smallest positive example yields the PAC learning algorithm. See the original notes here.

We introduce the following variables:

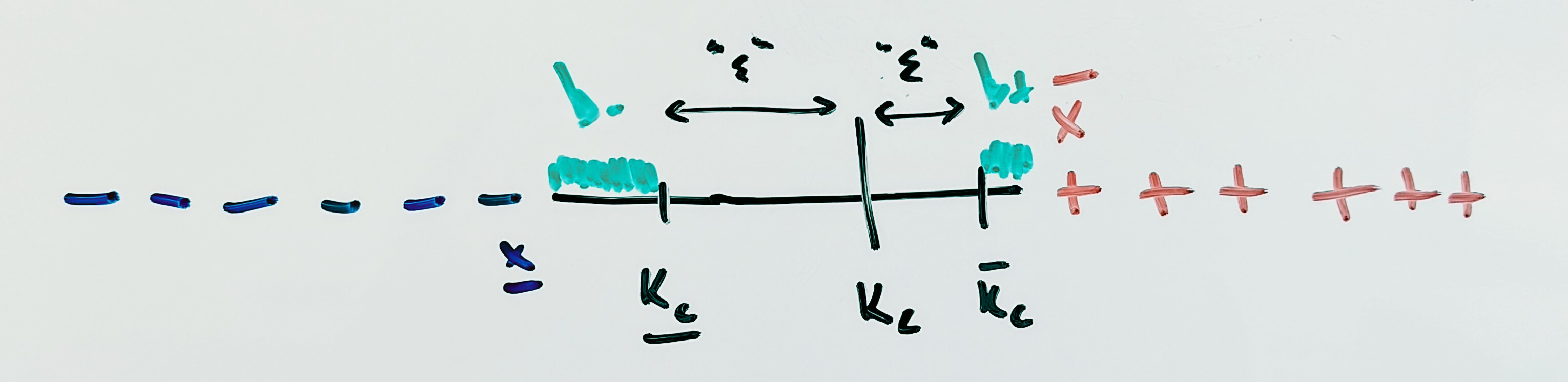

- $\underline{x}$ is the largest negative example, $\overline{x}$ is the smallest positive example, $k_c$ is the actual function, $\underline{k_c}$ is a number smaller than $k_c$ such that $\mathit{probWeight}[\underline{k_c}, k_c) = \epsilon$ and $\overline{k_c}$ is a number larger than $k_c$ such that $\mathit{probWeight}[k_c,\overline{k_c}) = \epsilon$.

- $R_- = [\underline{x}, \underline{k_c})$ and $R_+ = [\overline{k_c},\overline{x})$.

- After defining all necessary variables, we proceed to the proof.

- Let $h$ be a learned function where $k_h$ be an arbitrary number in $[\underline{x},\overline{x})$ ($h$ is defined by $input \geq k_h~?~true:false$). The proof is independent of how $k_h$ is chosen.

- Note that if $k_h \in [\underline{k_c},\overline{k_c})$ then $error_rate(h)<\epsilon$, we call this a “good event”.

- The good event happens when one of the following events happen: $k_h \in [\underline{k_c},k_c)$ or $k_h \in [k_c,\overline{k_c})$. These two events are mutually exclusive so the probability of the good event is the sum of the probabilities of the latter events.

- Dually, the good event does not happen when $k_h \in R_-\uplus R_+$, so there are two mutually exclusive “bad events”. Let us estimate the probability of $k_h \in R_+$. This event can happen only if none of the $m$ points fell into $[k_c,\overline{k_c})$, hence $p(k_h \in R_+)\leq (1-\epsilon)^m$. Similarly, the probability $p(k_h \in R_-) \leq (1-\epsilon)^m$. Therefore, $p(k_h \in R_-\uplus R_+)\leq 2(1-\epsilon)^m$.

- The probability of the dual (good) event is $p_{good} > 1-2(1-\epsilon)^m$. Since $(1-x)^m \leq e^{-mx}$, we get $p_{good} > 1-2e^{-m\epsilon}$.

- We want $p_{good} \geq 1-\delta$, which is achieved if we require $(1-2e^{-m\epsilon})\geq 1-\delta$, so: \(\begin{align*} 1-2e^{-m\epsilon} &\geq 1-\delta\\ \delta &\geq 2 e^{-m\epsilon} \\ ln(\delta/2) &\geq -m\epsilon\\ m &\geq \frac{1}{\epsilon}ln(\frac{2}{\delta}) \end{align*}\)

- Thus, if $m$ is at least as specified above, then $p(error_rate(h)<\epsilon) > 1-\delta$, which implies $p(error_rate(h)<\epsilon) \geq 1-\delta$, as required. Therefore, the space $H$ is PAC learnable, and since the number of examples is polynomial in the $1/\epsilon$ and $1/\delta$, it is also effectively PAC-learnable (under assumption that the learning algorithm itself chooses $k_h$ in polynomial time).

Note that the proof is generic and works independently of how the learning algorithm chooses $k_h \in [\underline{x},\overline{x})$. Its estimate of $m$ can be improved for specific learning algorithms: for instance, if the learning algorithm sets $k_h = \underline{x}$ or $k_h = \overline{x}$, then $m\geq \frac{1}{\epsilon} ln(\frac{1}{\delta})$.

#examples #learning #pac-learning #notes