Temporal Logics on Words with Multiple Data Values

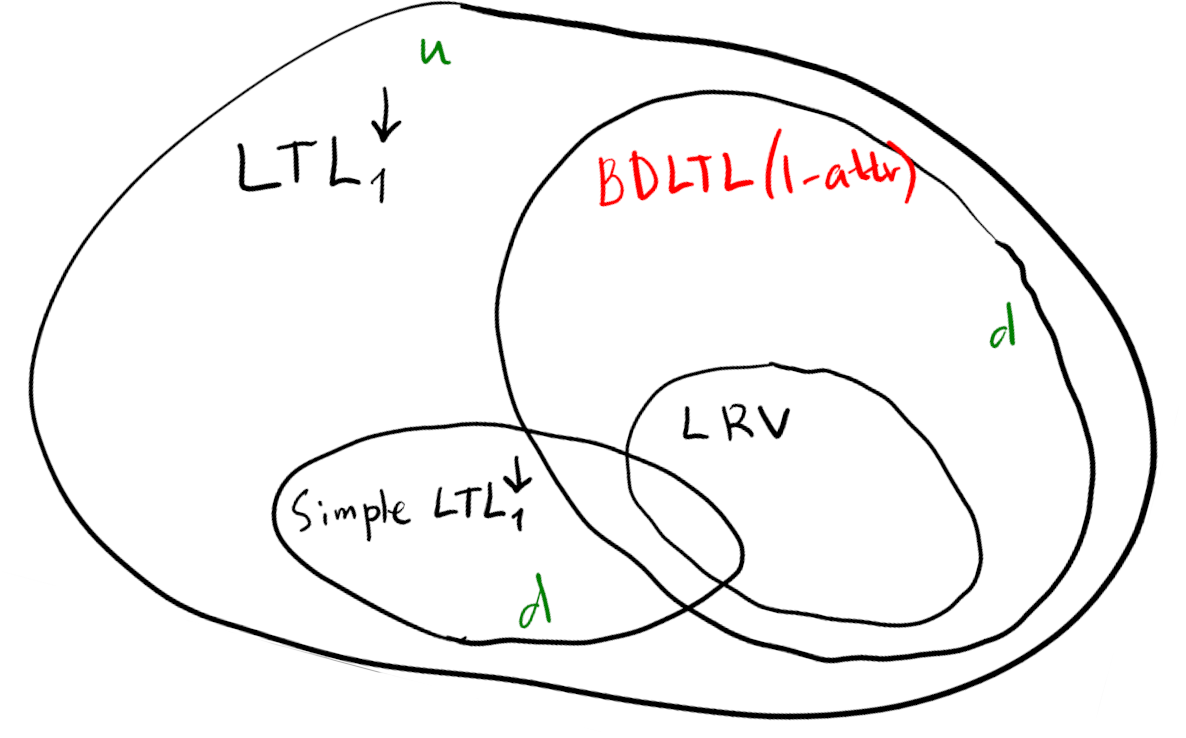

LTL logic data The logic BD-LTL (basic data LTL) is inspired by Freeze LTL, it more expressive but still decidable (‘d’ means ‘decidable’):

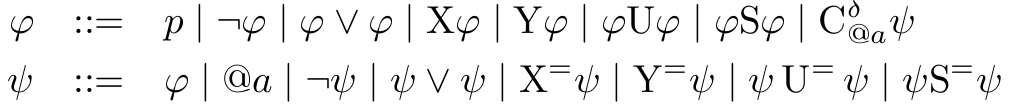

It works on finite or infinite words from $\Sigma \times D^{Attr}$, where $Attr$ are data attributes (i.e. variables). The grammar is:

It has a special operator $C^\delta_{@a} \psi$ which acts as a filter: take the data value $d$ of attribute $a$ in the current moment and evaluate $\psi$ on the trace in which at least one of the attributes (not necessarily $a$) has the data value $d$. For example:

- $@a$ inside $\psi$ holds iff the current value of the attribute $a$ equals the data value $d$;

- $X^=\psi$ holds iff in the next moment of the filtered trace the formula $\psi$ holds;

and so on. ($\delta$ in $C^\delta$ allows you to shift: instead of considering the value of $a$ in current moment, consider the value at moment $current+\delta$; seems that it cannot be emulated by $X$.) Note that the operator essentially cannot be nested (the grammar allows for this, but the semantics just takes the deepest one).

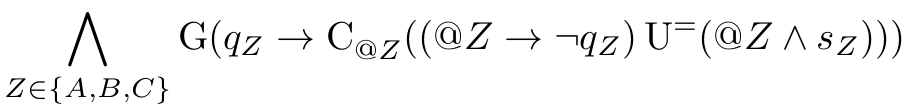

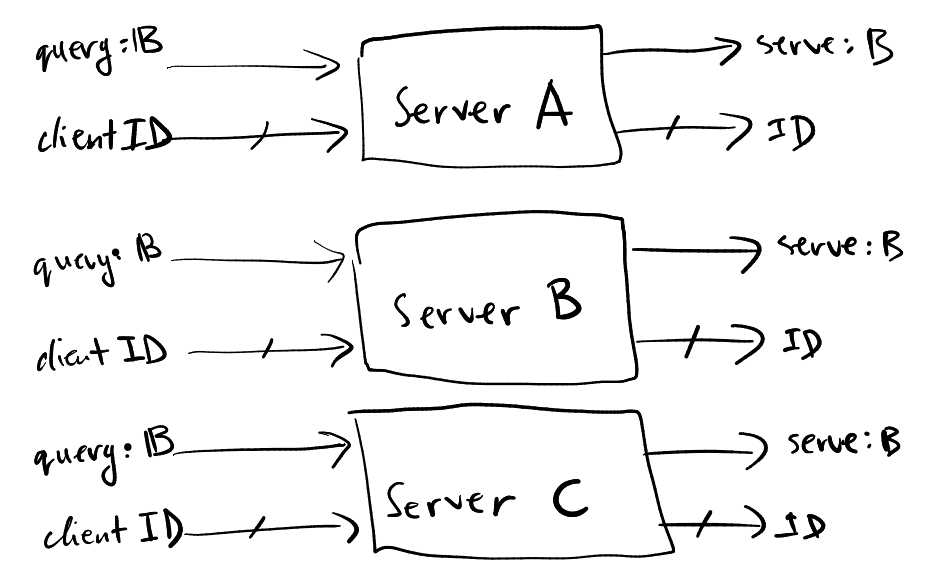

Examples. Let $\Sigma = {q_A,q_B,q_C,s_A,s_B,s_C}$ and $Attr = {A,B,C}$, where $q$ stands for ‘a query to the server’, $s$ stands for ‘serve the query’. There are three servers, $A$, $B$, $C$, and the data values model the client IDs requesting the servers.

This property says: if a client with id $@Z$ queried a server $Z$ ($@Z$ and $Z$ are not related, it is just a mix up of notation), then whenever client $@Z$ shows up in the trace it does not request the server $Z$ (but could request others), and this ‘whenever’ is satisfied until server $Z$ serves the client $@Z$. So, this is an assumption on behaviour of the clients. Another example: ‘every data request is eventually granted’ is encoded as $G(r \rightarrow C_{@a} F^= (g \wedge @b))$, where data inputs appear on attribute $a$ and data outputs on attribute $b$.

Results. They prove the satisfiability of this logic is decidable. The proof is by reduction to nonemptiness problem of data automata, and looks not hard. For the complexity, they say it is probably high. Then they show two undecidable extensions:

- $C_{@a,@b}$ instead of simple $C_{@a}$;

- the logic with operator ‘from-now-on’. They also consider some decidable extensions.

Here is one of their undecidable extensions that I looked into. Consider a new operator $C_{@a,@b}$ that allows you to fix two variables in the current moment and then filter the subsequent trace to have both data values to be present in some two variables. Note that this is truly an extension, since the original operator $C_{@a}$ does not allow for this (and nesting does not help). To prove undecidability of the new logic, they reduce PCP to it. Let a sequence of dominos \((u,v)_{i_1}, ..., (u,v)_{i_n}\) represent a solution to the PCP instance, where each $i_l$ describes the index of a domino (not the number of repetitions). We will use only two data variables, $a$ and $b$. With the solution sequence, we associate a word $w$ from $((\Sigma \cup \bar \Sigma) \times D^{{a,b}})^*$, where $\bar \Sigma$ are just barred sigma symbols and will be used for $v$-component of the dominos. We will use pairs of data values $(d^a_1,d^b_2)$ to address the individual letters in $w$. Recall that a solution the PCP instance has $u_{i_1} … u_{i_n} = v_{i_1} … v_{i_n}$. Their trick is to associate with $u$-sequence the data sequence $(d^a_1,d^b_1)(d^a_1,d^b_2)(d^a_2,d^b_2)…(d^a_{n-1},d^b_n)(d^a_n,d^b_n)$, where each $d^a_i$ occurs exactly twice except for $d_n^a$ which occurs once, the same for each $d^b_i$. Similarly, for the $v$-sequence. Morever, in the combined $u/v$-sequence, each pair $(d^a_i,d^b_{i+1})$ occurs exactly twice, once in the $u$-part and once in the $v$-part. Finally, the propositions of the-same-address labels should be equal (or rather whenever we see $\sigma$ for some $(d^a_i,d^b_{i+1})$ then later we should see $\bar \sigma$ in the same address). All these properties can be stated using the extended BD-LTL. Example: let the solution dominos be $(lo,l)(lo,ol)(lo,olo)$, where $\Sigma = {l,o}$. Thus, the $u$-part is $lo\cdot lo\cdot lo$ and the $v$-part is $\bar l \cdot \bar o \bar l \cdot \bar o\bar l\bar o$. With both $u$ and $v$ parts, we associate the data sequence: $(1,1)(1,2)(2,2)(2,3)(3,3)(3,4)$ (6 letters hence 6 pairs). The model of the formula will be: $(l, (1,1)) (o,(1,2)) \mid (\bar l, (1,1)) \ \sharp\ (l, (2,2)) (o,(2,3)) \mid (\bar o, (1,2)) (\bar l, (2,2)) \ \sharp\ (l, (3,3)) (o,(3,4)) \mid (\bar o, (2,3)) (\bar l, (3,3))(\bar o, (3,4))$, where $\sharp$ separates $(u,v)$ dominos and $\mid$ separates the components in a domino.

The main question is “Can we encode the same models using $C_{@a}$ only?”, i.e., without using pairs of data values? The answer is NO: the hard part is to ensure the correct order of data values. Suppose the $u$-part has data values $1\ 2\ 3\ 4$ and we want the $v$-part to have $1\ 2\ 3\ 4$. Seems like the BD-LTL cannot distinguish $1\ 2\ 3\ 4$ from $1\ 3\ 2\ 4$, while it can distinguish $(1,1)(1,2)(2,2)(2,3)(3,3)(3,4)$ from any of its shuffles. Nice.